Themes of technology and interaction have been woven throughout our programming since F-O-R-M’s inception. From interactive installations to multimedia dance works, to explorations of—and in—virtual spaces, we see a natural relationship between the body in motion and this branch of creation that takes movement-on-screen beyond filmmaking.

As a two year residency, our Technology & Interaction Artist-in-Residence Program, aims to support artists over a longer period of time, allowing more depth and breadth to learn new skills and integrate new technologies into their projects and practices.

Year 1: Research and Development

Year 2: Research into the realization of the project with a presentation at our 2025 10th annual festival

This year, we’ve been hosting our 2024-2025 Artist-in-Residence Katria Phothong-McKinnon, and her work in development titled IMPETUS.

To highlight the research and development phase of Katria’s first year in this program, our inaugural Artist-in-Residence, Jasmine Liaw interviewed Katria amidst this research. Take a read through this interview for a sneak peek at the work she’s been up to over the past several months!

Biography

Photography by jordan shum

Katria Phothong-McKinnon is a Queer Thai-Canadian artist navigating the blending of traditional and contemporary influences in her work. Originating from Calgary, AB, her practice includes sculpture, new media, performance, sound arts, music, dance and design. Rooted in Classical Thai dancing since the age of 7, she has expanded her dance practice to include street styles like W*acking, Voguing, Hip-Hop, and Popping. Currently based in Vancouver, BC, Katria is pursuing studies at Emily Carr University of Art + Design, majoring in New Media + Sound Arts with a minor in Curatorial Practices, and recently has worked/collaborated with Red Bull, Springboard Performance and the Esker Foundation.

Interview

J: Hi Katria, it’s so sweet to connect in this way, as both our performance practices are arriving into these interactive, embodied worlds. How is your artistic practice informed by sonic arts and new media, and intertwined with the body? Is there a memory or experience that sparked this interest?

K: Hi Jasmine! Yes, super lovely to meet you in person– happy we are able to meet up here in Toronto! This is an interesting question for me, many layers and arcs to this answer:

Growing up, music and tech were always around, even if it was the “low-fi” tech, like CRT TVs. I’d be fascinated by touching the static or hearing the hum when turning on the TV and wondering if others experienced it the same way. Those moments of curiosity became an inherent part of me. My interest in sonic arts and new media became clearer at university. I came in with plans to do music production but found myself experimenting with “cubes” and sound in different forms. To me, dance and music naturally intertwine with sonic arts and the body, and tech just amplifies that. I think about how turntables evolved into digital DJing—tech keeps reshaping how we interact with sound.

J: Oh, yeah, totally!

K: We’ve gone from vinyl to digital, which brings new experiences but also shifts how we connect to the music.

J: That’s so true in terms of these memory seeds in touching the TV, as a tactile and somatic connection.

K: Exactly, we’re now in this passive intake of tech and sound—listening to music just because it’s there. We don’t always have to dig deeper, but it’s worth thinking about. Even medical ultrasounds use sound frequencies to explore the body. That tactile and analog quality—like vinyl or cassette tapes—is a whole different experience compared to digital. Listening to vinyl, for example, feels more intentional; there’s something ritualistic about placing the needle and waiting, compared to instantly streaming a playlist. That instant gratification affects our attention spans, which is great for the music industry but maybe limits us as listeners. We’re kind of cyborgs now, right? Even my glasses—without them, I’d be completely lost. We’re more connected to these things than we realize.

J: Yes, that connection to material really impacts how we navigate our bodies, almost like operating technology.

K: Yeah, and on the flip side, I just think sounds are cool! Circuits are visually interesting, and I like how tech encourages us to move our bodies. But we’re a pretty sedentary species, so movement feels necessary—even if it’s just hitting “play” or pushing a button.

J: Yeah! So, when thinking about interactivity, who or what is the “cube” for you? What does this world of the cube embody?

K: My piece “IMPETUS” or The “cube” is all about grids—a structure every new media person loves! Tech is organized in this way, from ones and zeros to the square format of social media feeds. Our screens are squares, and it’s funny to think about how tech design shifted. In the early 2000s, like with the N64, you could see all the circuits inside. Now everything is hidden. It’s like we’ve moved away from showing the “how” behind tech to just appreciating the shiny final product.

J: Yeah, hiding the mechanisms to make it functional and valuable.

K: Exactly—the polished “shiny rock.” I’ve always wondered when that shift happened because I thought exposed hardware was really cool.

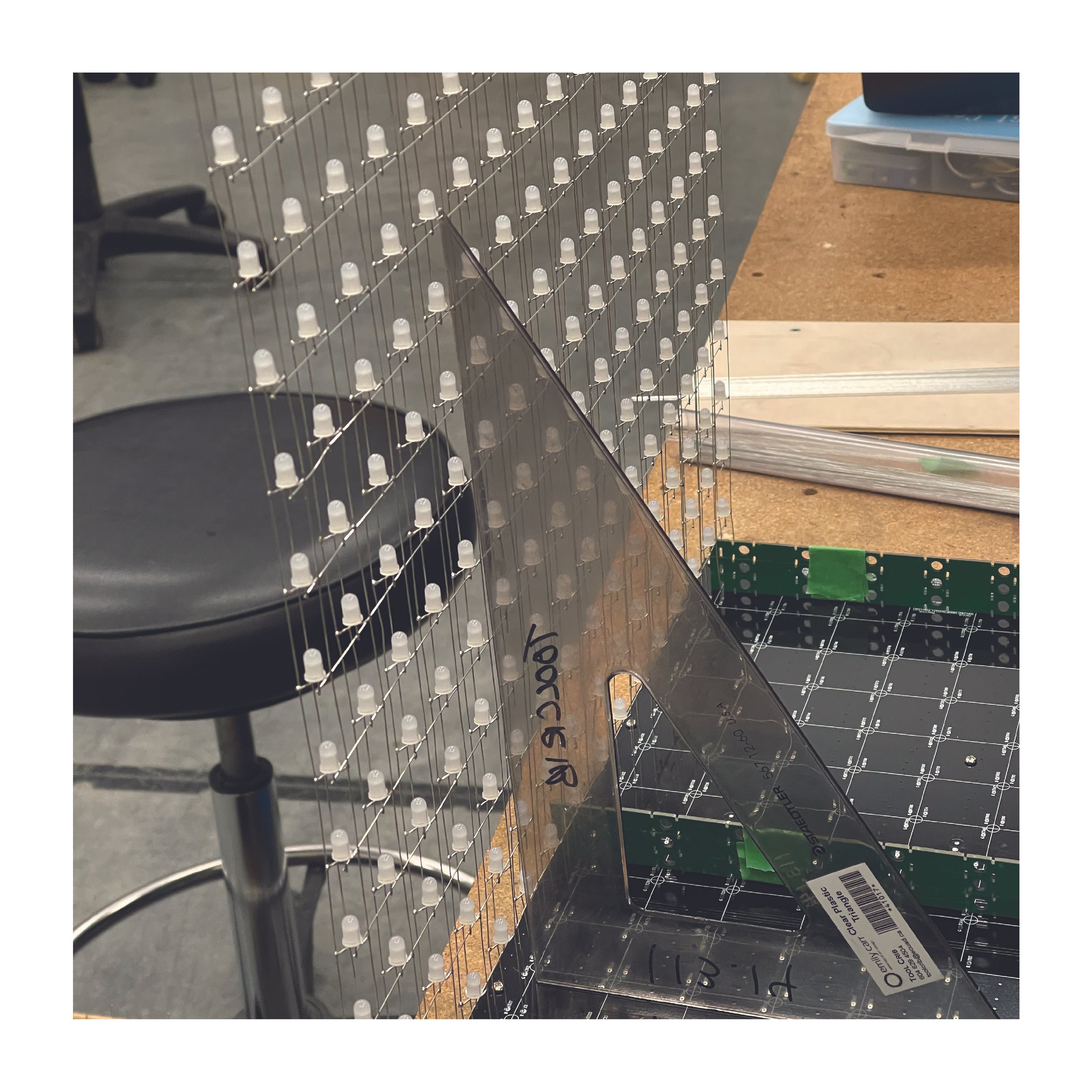

J: So you’re creating this cube out of LEDs. Can you tell us about the process?

K: The first cube I made was really an exploration. I hand-soldered each LED—4096 of them with four legs each. It took a long time and didn’t turn out perfect, but that was the point. I wanted to experience the labor and imperfections firsthand. There’s a value in building and engaging with tech physically, even if it’s painful and repetitive, like sitting in a “shrimp posture” for hours. It’s a reminder of the body’s role in this tech-driven process.

J: Right, so you’re creating awareness of labour and bodily engagement. What do you want audiences to see in this work?

K: I want them to see the imperfections in the soldering—the human traces in the tech. Tech is often presented as pristine and mysterious, but I think mistakes make it more relatable. I’d love for people to consider tech more actively, even if it’s usually passive. This is especially true in digital spaces, where moments in dance or performance are fragmented. Watching a clip online doesn’t capture the same energy or crowd interaction as being there in person. It’s a sliver of the full experience, and while it’s accessible, it loses the depth of the live moment.

J: So many things just came up, and so many questions were answered in between. The rawness and exposure of the circuit feels like an unravelling of the body as a structure. I love your approach to embracing failure — it’s refreshing that you’re engaging with the labour and hard work rather than outsourcing it. What does the next stage in your research look like within this residency?

K: The next step is scaling up to a bigger cube, and with that, I’m diving into Touch Designer. For this phase, we’re ordering the cube, so I won’t be soldering it myself. That’s my limit, and it’s where I trust someone else’s expertise. I see this as a two-part project, almost like a diptych: one cube is my handmade piece, full of imperfections, and the other is this highly manufactured object that does what it’s supposed to. I’d love to present them together as two parts of a larger narrative.

J: Would you display them together?

K: Yes! I think they’re more meaningful as a pair. Each tells a different story, and they complement each other, almost like two sides of the same transformation.

J: And how do you envision your physical body in relation to both pieces?

K: The main idea for the larger cube is to use volumetric or other types of movement data to project my body into a fragmented matrix space. It could stretch and abstract my form or represent it more directly. Either way, I’m present in both pieces—the one that’s “lit up” and the one that’s not. There’s a presence in tech that goes beyond the visible; it’s like when we consider the materials in our devices, the labor, the origins we often overlook. Dionne Brand’s Salvage inspired me here. She discusses how life is present in silences and inanimate things, even in the narratives that exclude certain voices. Similarly, there’s a human presence in tech that we don’t always acknowledge unless we consciously look for it.

J: Yeah, it’s like an in-between space.

K: Exactly. I’m just as present in the first cube as in the second, whether it’s visible or not. It’s not just me either—there’s also the circuit board someone else designed. I may never know who, and I’m okay with that. I’m thinking a lot about opacity—the right to choose when and where to be seen. It’s freeing not to always be the focal point, and with this project, I can step back and let the work stand on its own.

J: I love how you’re exploring performance as something beyond a central, “witnessed” event, blending it with technology in a way that’s interactive. This project is clearly so intentional, down to the epigenetics of your body, resonating with your background and movement choices. Are you using motion data?

K: Yes, that’s the plan. We’re experimenting with Kinect data, though I’m also curious about the limitations of a basic webcam. Tech moves so fast; even a simple camera now can capture motion in new ways.

J: And with AI and lighting, it’s constantly evolving. I can see how this connects to your work with light and visual intention. What are you envisioning for the motion data and movement?

K: Conceptually, I’m always thinking about fragmentation—ones and zeros; social media’s effect. I love sharing snippets of my life, but it’s also a reminder that each photo or post reduces me to data. It’s like putting myself into numbers, while still wanting to be seen as more than a number. I think of it like those sci-fi scenes where someone steps into a space and becomes particles—abstracted, yet whole. There’s beauty and complexity in being perceived in these fragmented ways.

J: Yeah, it’s like an in-between space.

K: Exactly. It’s both exciting and complex to be seen that way, and I’m okay with that ambiguity.

J: It’s interesting that you chose LEDs as a material—they seem so connected to the data and movement they express.

K: Yes, everything’s connected, whether we like it or not. I even appreciate the possibility of burnout—it’s real and kind of visceral. For example, the top two rows of my first cube burnt out, and it felt like a “health bar,” like I’d lost a bit of life from this labour. I have other projects outside this one, including some school work exploring ideas of honouring land, like how spirit houses in Thailand create space for spirits. I wonder if we could bring that same sense of respect into digital spaces—where a memorial Facebook page, for example, occupies physical land somewhere on a server. It’s complex, but I think about how these acknowledgements might extend into digital realms.

J: I appreciate how your work is layered and transcultural, touching on so many aspects of existence. You’ve mentioned the violence within tech, and it reminded me of the film Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner — an Inuit folklore story with no strict protagonist or antagonist, resisting binaries and leans into the plurality of both.

K: That’s powerful, this plurality of negotiations and relationships. It’s refreshing to see “decolonization” not as a fixed solution, but as an unraveling and understanding of past and present simultaneously.

It’s not just about “what do we do now?” but exploring and recognizing how these histories coexist. There’s a place for joy and happiness in that process too. It’s easy to stay in a constant cycle of reliving generational trauma, but I think we’re also allowed to live fully now. As women of color, as queer people, we face specific challenges, but acknowledging what’s good and finding joy despite it all is meaningful.

J: It’s like holding both grief and happiness in the same space.

K: Exactly. We can acknowledge our histories without feeling guilty for enjoying what has been a result of them. For instance, my grandmother had to hide during Japanese invasions, which left complex feelings, but I can still enjoy Japanese food and media without guilt. There’s also a weird balance with institutional spaces, like universities. I’m aware of their colonial legacies, but having a degree or finding value in structure doesn’t make you entirely complicit. It’s okay to engage with these layers without carrying guilt for every enjoyment.

J: I love how the scale and multiplicity of the LEDs reflect the complexity of the body—all the different elements working together. And then there’s the light, which seems to embody the joy you spoke about in celebrating our full selves.

K: Yes, but light also needs darkness to be visible. It’s like how we find joy alongside sadness. I’m creating a soundscape for the piece as well, so it’s not just silent. Ideally, I’d love to display it in a spatial setup, like in a spatial sound environment, for an immersive experience that still feels slightly disconnected.

J: Thinking about sound in space, what ideas and thoughts come up when you’re integrating sound into your project?

K: I’m thinking of surrounding the space with sound. I enjoy creating tangible, immersive installations that let people feel like they’re stepping into another world. I’ve even considered adding a scent element, inspired by a Thai artist who used incense ashes to evoke memory and heritage in her work. But for now, I’m focusing on making it a multi-sensory experience, where the sound and light interact.

J: Woah yes! That awareness that sound really is sensorial! How many speakers are you considering?

K: I’m thinking of a four-channel setup, maybe adding transducer speakers to create vibrations on the floor. I love sound that you can feel physically—sitting on a subwoofer at a club or experiencing low frequencies that resonate through the body. Different frequencies hit us in unique ways: bass is felt in the chest, while higher tones feel lighter, more heady. These nuances are central to the soundscape I’m creating, aiming to bring out that visceral quality of sound.

J: It’s fascinating to think about sound as pure vibration. Instead of just creating an atmosphere, you’re really making it tangible, especially in how it interplays with your movements.

K: Exactly! I want to capture those specific tones and notes that resonate, the ones that just hit right. It’s the same feeling I get in dance—certain songs just make you want to move, while others feel flatter. It’s about capturing that energy and letting each visitor experience it differently based on the space and the setup.

J: It’s wonderful to see how your dance practice informs your sound work. You’re creating this reciprocal relationship between movement and sound, almost like a feedback loop.

K: Definitely—it’s like a system within a system, constantly looping back. Even in complete silence, there’s feedback from your own body, your breath, the tiniest sounds around you. It’s a reminder that we’re always immersed in a web of feedback, which is essentially what dance and tech are. It’s like a series of Russian dolls, where each layer contains yet another layer of sensory experience.

J: It really captures the “aliveness” of being present in your body. And having a mentor like Cristian Gonzalez, must be so helpful in navigating these layers.

K: Yes, working with Cristian has been transformative. He’s brilliant, and having his guidance makes me feel less isolated in this process. I’m used to working solo, doing everything myself, which can feel overwhelming. But Cristian’s expertise has been invaluable, especially since we’re both exploring new territory with this cube. It’s like a breakthrough every time we talk—he helps unravel ideas I was stuck on. This level of mentorship, where someone truly understands and supports what you’re doing, has been a game-changer for me.

J: It sounds like his knowledge really compliments your vision.

K: Absolutely. Collaborating with him, and learning from him allows me to focus on the core of my work without feeling lost in technical details. There’s something special about having someone who can answer even my “dumbest” questions without judgment. I haven’t always felt that kind of support in other settings. Cristian’s mentorship has been exactly what I needed to take this project further.

J: When you’re thinking about exploring digital and physical world-making, what extensions of your transcultural identity have surfaced or are surfacing?

K: When I’m exploring digital and physical world-making, a lot of layers of my transcultural identity surface in ways I’m still uncovering. Growing up in Canada with strong Thai roots, I find myself constantly balancing these worlds, questioning what "belonging" means in physical spaces, like land and community, and in digital spaces that we occupy so fluidly.

There’s also this feeling of connection and tension when I use LEDs. LEDs reflect a kind of delicate structure, almost fragile, like my own experience of navigating different identities and cultural codes. Using such a material feels like I’m embodying that code-switching aspect of my life, where I’m continuously shifting between identities depending on the space and what it calls for. In a way, this fragility and the need for constant adjustment mirror my experiences with transcultural identity—balancing aspects of tradition and modernity, of seen and unseen labour, of digital and physical realms. It’s a way of integrating all these facets, and instead of presenting one clean, perfect narrative, I’m able to embrace the multiplicity and the “in-betweenness” that comes with it.